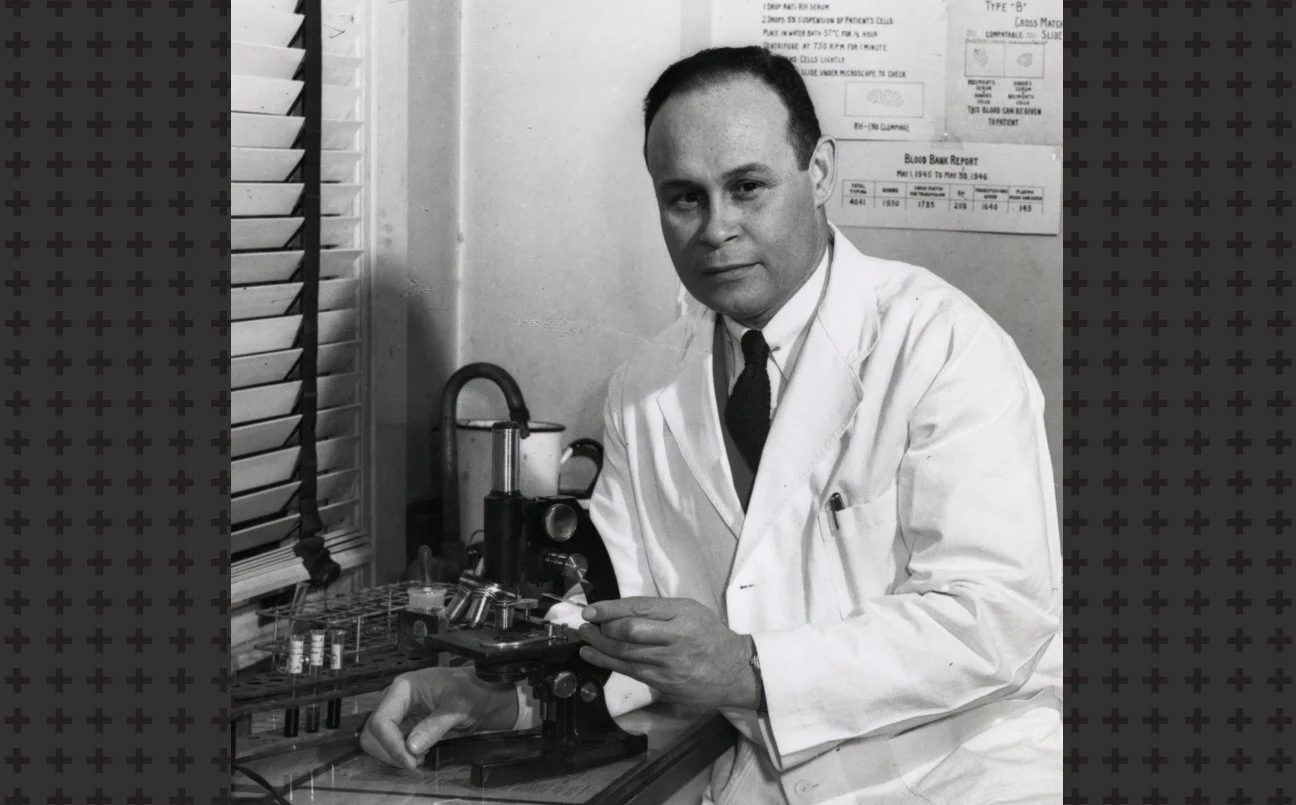

Charles Drew in the lab at Howard University, 1942. Photo credit: curlock Studio Records, ca. 1905–1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

As we celebrate Black History Month, it’s important to pause and remember the achievements of Black Americans and their critical, central role in United States history. Here, we spotlight Dr. Charles Richard Drew who, in the face of much adversity and segregation, first discovered a method for long-term storage of blood plasma and organized America’s first large-scale blood bank. This not only saved thousands of lives during WWII, but also standardized long-term blood preservation techniques used by the American Red Cross.

Medical Career and Professional Life

In the early to mid-1900’s, the field of medicine was greatly limited for Black Americans. As one of 13 Black Americans in a student body of 600, Drew began his undergrad education in 1922 at Amherst College in Massachusetts. During his residency at McGill University College of Medicine in Montreal with his professor John Beattie, his interest in transfusion medicine began. Beattie trained Drew on ways to treat shock with fluid replacement. Drew then went on to work as a pathology instructor at Howard University College of Medicine.

In 1938, Drew was recommended and assigned a Rockefeller fellowship under John Scudder in experimental blood bank work at Presbyterian Hospital in New York while he earned a doctorate at Columbia University. During this time working with Scudder, Drew conducted extensive original research on blood chemistry, fluid replacement, and variables affecting blood preservation, culminating in a seven-month trial blood bank that was a great success. Drew was considered by Scudder as a “naturally great” and a “brilliant pupil”. Drew based his seminal dissertation on this research titled “Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation." Scudder called this thesis “a masterpiece” and “one of the most distinguished essays ever written, both in form and content.”

During WWII, Drew was chosen to lead a U.S. relief program known as the Blood for Britain project (BFB) where blood was collected, and plasma was sent overseas. Drew, along with Scudder, and E. H. L. Corwin planned the safe process of extracting, collecting, processing, storing, and transporting contaminated-free plasma for Britain’s soldiers. Using centrifuging and sedimentation techniques, they were able to separate plasma from blood cells and preserve it against contamination. Plasma was ideal for the battlefield in that it could be used as a substitute for blood, could be used on any blood type, and was less likely to transmit diseases. It was also better for transport due to keeping longer without refrigeration and deterioration.

While leading efforts for the BFB project, Drew passed the American Board of Surgery exams with a ‘legendary’ oral portion in which he gave a lecture on the fluid balance and management of shock. After being called back to Howard briefly, Drew continued to supervise the BFB project which went on to become the model for the mass production of dried plasma via a pilot program of the American Red Cross. Drew became the assistant director of this undertaking, later becoming assistant director for the National Blood Service. During this time, Drew invented mobile blood donation trucks with refrigerators known as “bloodmobiles” which earned his title “Father of the blood bank.”

In 1941, Drew went back to Howard University for the next nine years to pursue his passion and life-long goal of helping Black Americans advance their rights and careers in medicine. Soon after returning, he was appointed Head of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen's Hospital. In 1948, his first group of surgery residents passed their board exams. Drew believed his greatest mission and “greatest and most lasting contribution to medicine” was to “train young African American surgeons who would meet the most rigorous standards in any surgical specialty” and “place them in strategic positions throughout the country where they could, in turn, nurture the tradition of excellence.”

At the age of 46, Drew tragically died in a car accident after falling asleep while driving to a conference.

Overcoming Adversity

Like fellow Black Americans, Drew faced adversity and discrimination at every step of his personal and career development. In 1922, on a football and track and field scholarship by Amherst College, despite being his team’s best football player, he was overlooked as captain while also facing hostility from other teams. After receiving his MD and CM (Master of Surgery) degrees in 1933, Drew was barred from continuing his training in transfusion therapy at the Mayo Clinic because of racial prejudices. In 1938, during his fellowship in experimental blood bank work at Presbyterian Hospital in New York, he was prevented from the many privileges of his white peers like having direct access to patients. And even though Drew helped direct the program and his work became a model for the Red Cross’ mass production of plasma in 1941, he himself was excluded from donating blood because of his skin color. After much advocating, Drew resigned in 1942 after the armed forces ruled that the blood of Black Americans would be accepted but would have to be stored separately from that of whites.

- At the McGill University College of Medicine in Montreal

- Won the annual scholarship prize in neuroanatomy

- Elected to the medical honor society Alpha Omega Alpha

- Won the J. Francis Williams Prize in medicine after beating the top 5 students in an exam competition

- Received his MD and CM (Master of Surgery) degrees, graduating second in a class of 137

- The first Black American to earn a medical doctorate from Columbia

- Won a fellowship to train at Presbyterian Hospital in New York with eminent surgeon Allen Whipple

- Supervised the Blood for Britain project (modeled after Drew’s research) which collected 14,556 blood donations and shipped (via the Red Cross) over 5,000 liters of plasma saline solution to England

- Advocated for authorities to stop excluding the blood of Black Americans from plasma-supply networks

- Appointed Assistant Director of the First American Red Cross Blood Bank (1941)

- Invented the first mobile blood donation trucks with refrigerators

- Earned the title, “Father of the blood bank”

- Appointed Head of Department of Surgery at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Chief Surgeon at Freedmen’s Hospital (1941)

- Awarded E. S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science from the John A. Andrew Clinic in Tuskegee, AL (1942)

- Appointed Chief of Staff at Freedmen’s Hospital (1944)

- Awarded Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for his work on blood plasma (1944)

- Awarded honorary doctorates from Virginia State College (1945) and Amherst College, his undergraduate alma mater (1947)

- Elected fellow of the International College of Surgeons (1946)

- First Black American to be appointed Examiner for the American Board of Surgery (1948)

- Appointed Surgical Consultant for the United States Army's European Theater of Operations (1949)

- In addition to training young Black American surgeons, Drew campaigned against the exclusion of black physicians from local medical societies, medical specialty organizations, and the American Medical Association

The life of Dr. Charles Richard Drew needs to be remembered and celebrated. Despite much adversity, not only did his brilliant work and research save countless lives then and now, he used his talent to advocate and forge a path for others to do the same.

Stay informed on the latest trends in healthcare and specialty pharmacy.

Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter, BioMatrix Abstract.

By giving us your contact information and signing up to receive this content, you'll also be receiving marketing materials by email. You can unsubscribe at any time. We value your privacy. Our mailing list is private and will never be sold or shared with a third party. Review our Privacy Policy here.

Sources and further reading:

Charles Richard Drew. ACS. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/african-americans-in-sciences/charles-richard-drew.html

Charles Richard Drew. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Richard-Drew

Charles Richard Drew. Science History Institute. https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/charles-richard-drew